Our thoughts - Josef Fischer

2021-06-10

This month, I want to share some reflections about our work inspired by the book “How the World Thinks” by Julian Baggini, a philosopher and writer, which brought to life some of the shadowy assumptions we all make and continue to make in our everyday work here at the Centre.

A main strand of our work at the moment is developing a set of measures that we think capture the essential elements of evaluation in a youth provision environment. We believe it is important to understand the social and emotional skills of young people when they first engage with provision – what they’re bringing with them - and when they leave – what they’re taking out into the world. We also think asking for feedback from young people about their experiences in provision is critical and asking staff to reflect on the quality of their provision in a learning environment cannot be forgotten. We have a reasonable set of evidence gathered from our work in the Youth Investment Fund that has underpinned and given us confidence in our measures.

I have been building the digital implementation of these measures. That has filled the last few months with data types, coding structures, logical relationships between variables as well as almost every error message possible thrown up by my recalcitrant computer. Usually this is followed by a demo and another iteration – with the determination that we will alight on what it is we really want our users to experience and interact with. I like to think of it as spinning a web to capture a particular story.

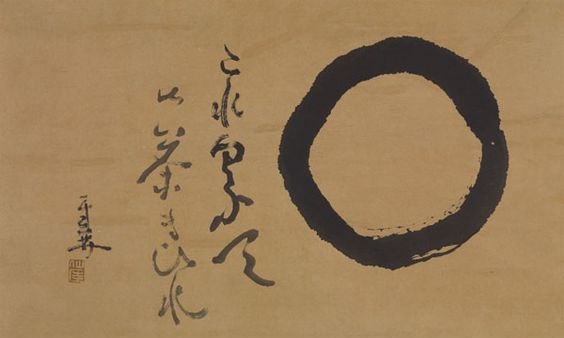

It is this idea of a web that reminded me of Baggini’s book. He wrote that Western cultures tend to look at the properties of things (concepts or objects, for example) whereas in Eastern Asia the focus is more on the backgrounds to things and what sits between them. Thus, the relationships between objects are as important as objects themselves, something that tends to be undervalued in the West where the focus on outcomes and ‘productivity’ is paramount. A painting by Gibon Sengai, a Japanese aesthetic artist, of a circle with two lines of calligraphy on each side illustrates the point. Baggini writes that Americans first describe the painting as a circle whereas East Asians describe a space enclosed by a circle as frequently as the circle itself. I was vaguely aware of this already, but never really appreciated the implications of it for our work.

Our measures are our ‘web’, and they have certain properties such as validity, reliability, usability and so on. But we also relate the variables or observable things in our measures to each other: this is after all where we expect their power to come from, and why it is a web rather than a series of independent views represented by the different instruments. I have been busy coding this ‘web of things’ developed by the team to capture the narrative of quality provision leading to more positive outcomes for young people. Our digital platform should make it easier to view and analyse the relationships between these concepts, and I believe that understanding the relational aspects of the data we collect deepens our understanding and helps us build better relationships with young people.

Baggini made me wonder whether there are further stories told by the spaces and patterns between the strands of our web that are just as valid and true but that we have not yet seen because of our cultural lenses. To me, this thought is both disquieting and motivating. I want to know what we may have missed simply through wearing a particular cultural set of lenses and I’d love to hear from you if you find yourself using our tools and think there is uncaptured story. Your contributions will help us broaden, deepen and make our tools more sensitive to the diverse realities experienced by young people.